Generalisation and Stereotype

To begin, a qualification of what follows, i.e. notes on what the French have come to represent in the mind of your Friesian writer. I have been both a philosopher of sorts, and a social scientist. The word ‘scientist’ needs emphasis; not from pride, but because there are many who do not consider sociology a science.

A case in point. Someone I know, ridiculed the idea of sociology being a science, arguing that at the university where she had studied there had not been such thing as a faculty of social and political sciences. She meant Oxford. Funny it is that, of all things, she had been studying English literature, which may at best be considered unscientific meddling with other people’s language, an interference pimped up by a few hyperbolical ‘theories’ like semiotics and structuralism, and why not, even by a sprinkling of Lacanian psychoanalysis. Language studies do not inform one about what scientific research is all about; and certainly not how difficult it is to do sociological research. What all this the would-be ‘theory of literature’ has to do with literature is a thing that has remained a mystery for me; yet, I have also read my Eco, my Barthes, my Levi-Strauss et cetera – rather extensively so. To ‘study’ literature is basically an essay in using one’s memory; yet, literature has been written to be loved ad appreciated.

That someone, coming from the country where Mrs. Thatcher once ruled, can claim that sociology is not a science, is not at all surprising. According to that unpleasant woman, ‘there is no such thing as society.’ Thatcher had also studied at Oxford: chemistry and law. Thus, she also had not an inkling of what sociology might have taught her, the kind of knowledge which could have prevented her from her disastrous social and economic policies that have, until this day, wrecked the social structure of her country.

Sociology is quite different from law, and from both chemistry and ‘analysing’ literature. The reader might be interested in what in the eyes of a Dutchman it is to be ‘French’, more precisely, in the eyes of a Friesian who has descended from pirates. Thousands of years ago, bands of the Friesian tribe were raiding the Romans who, at the time, were occupying half of Europe’s continent; they made their sorties by water or by land from the wet lands just north of the limes, the Roman frontier which ran from Holland’s Lugdunum Batavorum or Leyden, to the Russian Black Sea where emperor Augustus once exiled his greatest poet Ovid.

For a better understanding of my ideas, it is good to differentiate a stereotype from a sociological generalisation. I won’t go into the marvels of Luhmann’s systems sociology; take it from me, that by reading his work one may understand a few things a bit better. The one thing I would like to stress, is that too think sociologically, one is always generalising. That may be a sin for the student of literature for whom a novel or a poem is always ‘unique’, even though – paradoxically so – their general ‘theories’ are supposed to suspend this uniqueness; yet, to generalise about group behaviour is the only way to think sociologically, even if in this piece I do not use statistics, and I did not perform any real scientific research.

Gauging the French

Gauging ‘the French’ took this Friesian a while. I have lived in this country for twenty-five years; first, four months a year; later, almost half a year; then, the last four years, full time. I shall just touch upon what I have come to consider as the core ‘soul’ of this funny nation. Because funny they are, the French – funny in a way… Just think about the fact that immediately after Brexit, they proposed to re-introduce French as the Esperanto of the European institutions, to replace the English language which everybody is actually speaking, and which is generally spoken there – even by the French, in a way…

Yet, a stereotype is not a generalisation. To make things a little awkward, I quote from Wikipedia: “In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example, an expectation about the group’s personality, preferences, appearance or ability. Stereotypes are often overgeneralised, inaccurate, and resistant to new information. A stereotype does not necessarily need to be a negative assumption. They may be positive, neutral, or negative.”

This description defines a stereotype as a kind of generalisation; one, that is not necessarily negative, but one that tends to ‘overgeneralise.’ It is also ‘resistant to new information.’ Yet, precisely being capable of correction makes a generalisation as to people’s behaviour sociological, thus not a stereotype. It is also doubtful to speak of ‘overgeneralisation’: generalisation is always stating something about whole groups of people, without taking into account individual specimens, or claiming that one might predict an individual’s specific behaviour. What Wikipedia tries to convey, and where it caters to a widespread prejudice, is that individuals are actually too important to fall under the heading of generalisations. However, no proper endeavour to generalise involves the description of an individual; it can merely tell the probability of how members of a certain group tend to react to certain stimuli. A proper, research-based generalisation also gives a theoretical explanation for this expectation.

From what follows, it will become clear that, re: The French, I did not do any sociological research; thus, my supposedly proper generalisations may turn out to be stereotypes; it is the risk I run. Yet, over my twenty-five years of living here, I did indeed change my view of ‘The French.’ The reason is twofold: first, I changed my status from someone temporarily living in a small hamlet, in which were living only a few Frenchmen most of whom became friends, to living in a small provincial town with lots of other foreigners; secondly, living here as a resident brought me into close contact with many more types of Frenchmen, and what is more, with French functionaries populating the state institutions: tax office, gendarmerie, people at townhall, you name it.

Jealousy and Rancour

My only living French friend has opened my eyes; two years ago, at a Christmas dinner party, he told me that Frenchmen are fundamentally jealous of one another – envious. I simply had missed this before, living and hiding as I had been in my little hamlet. Ever since that dinner, I have spent many an hour pondering the issue which seems to be at the heart of what it is to be ‘French’, and which explains much of their behaviour. Why should jealousy in one nation be rampant, while in another one, for instance in my own country The Netherlands, a generalisation like this could never have been made? The explanation seems to be two-part.

First, we had the French Revolution, which according to the creed finished with royalty by beheading the king and his family. By the time King Louis XVI lost his head, he had already been thrown out of his royal office, demoted to the rank of Citizen, named Louis Capet. Many Dukes, Barons and Marquises had gone before him, their heads rolling in baskets full of sawdust. As a Frenchman puts it succinctly: Tout à coup, by way of a simple political decision supported by a sharp blade, all in one blow, just as speedily as Louis lost his head, as well as his newly acquired title of Citizen – the very moment, humane Madame la Guillotine separated it from his body. Once again, phrased so well by a fellow Frenchman: ‘Speedily – in the wink of an eye.’

Thus, ends life in revolutions. At a quarter past ten, in the morning of the 21st of January 1793, Capet’s orphaned head toppled in the sawdust. We have a picture of the (in)famous ‘ostentation’: the showing of the decapitated head of citoyen Capet to the masses, blood dripping profusely from his severed neck, to prove that it was finally over.

.

.

Yet, paradoxically so, it was not over; the Revolution did never end. The beheading of their king had far-reaching consequences in the lives of the common men and women of France. One of these has been the mentioned pervasive jealousy. After the Revolution, instead of really calling it a day and leaving royalty behind forever, each Frenchman suddenly felt entitled to feel himself a king. The presence in one country of a million kings places each single citoyen in a pragmatic paradox: he is supposed to be ‘equal’ to all others citizens, as well as their broth, but at the same time he feels entitled to royal prerogatives. This implied, that no Frenchman should have a penny more than another Frenchman; nor a larger house; nor a grander garden; nor a higher function – et cetera. The fundamental jealousy of the French was born.

After the Revolution, the French State was, and is still suffering from its Sun King Complex; no revolution could change that. In the French language this is known as le complexe de chef. Since that infamous end of the 18th century, times about which the Irishman Burke wrote so well, every Frenchman wants to be king, or for that matter a queen. This naturally turns the society into a nuthouse. “I am the Queen of France.” “No, Sir, it is I who am the Queen of France” et cetera. Out here, just you try participating in traffic…

.

.

Any Frenchman shits in his pants when he meets a figure with power, whether it is the president himself, a policeman in the street, an official in one of the many state offices, or a politician. Watch French television; when confronting a politician, interviewers become intimidated, as well as visibly horny; obviously, the politician is never really confronted.

This is an utterly formalistic and authoritarian society, and in this Brave New World this may spell the downfall of its economy. Almost nobody here speaks anything but French, even if they think so differently themselves. Any decision here seems to be a French decision; so, fuck the rest of the world. A bit Trump-like, perhaps. In postmodern capitalism, global and flexible as it is, there is no place for such solitary French decision making.

By way of his Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche has given us the second half of my explanation. Basic jealousy it was from the start; then something decisive happened: it turned into rancour, which is a very different cup of tea or, to phrase it the American way, a whole different ball game.

One should not forget that Nietzsche was first of all a sociologist of morals, not a psychologist. He filleted the ‘English historians of morals’ who were indeed philosopher-psychologists, who had reduced the notion of what is ‘good’ to a utilitarian psychology. Utilitarianism claims that what is considered as ‘good’ has originated in useful altruistic acts. On the contrary, thus Nietzsche, ‘good’ has always been what the powerful, the noble and the higher placed considered as good, that is: everything they stood for. (§2)

Yet, it seems correct to call Nietzsche also a great social-psychologist, as he was interested in how this hegemony of morals, to use a phrase coined by the Italian communist Antonio Gramsci, has been transformed, how the underlying classes came to experience the upper-class morals, developed by the powerful. What I described as the basic jealousy of the French, has transformed into rancour or ressentiment. I prefer my own metaphor of the pressure cooker, in which jealousy is put to simmer on the fire, heating up, yet not able to get out. Nietzsche phrased it well: ‘The ressentiment of the kind of people who are denied a real reaction – the reaction of the deed, of the act.’ (§10)

People become rancorous, being first jealous of all others and of everything those others own and do, but merely able to observe these differences, without getting a chance to vent their anger. That has been the situation in post-Revolutionary France and ever since: all Frenchmen being considered equal, as well as brothers in freedom, yet all of them feeling like kings, none of them can act out this jealousy, or it must be in devious ways.

Nietzsche claimed that in the common man rancour ‘poisons the eye.’ Which brings us to what I consider the peculiarities of the French. Nietzsche was, of course, writing about 19th-century rabble, ready to revolt like the slaves, ‘full of voluptuous greed, gall-like jealousy and an embittered need for revenge.’ (Zarathustra, part 4) This also applies to the present-day French. In his Genealogy of Morals, he would sum this up: ‘The revolt of the slaves of morality begins with their rancour becoming creative, bringing forth values; the rancour of those, who are denied the true reaction of the deed, who can only consider themselves to be compensated by their imaginary revenge. Whereas a proud, noble ethics consists in a triumphant yes! to oneself, slave morals always imply saying no! to what is not their own self.’ (First Treatise, §10) Nietzsche’s solution to this problem is told by Zarathustra who, with a wink at Sokrates, preached ‘that one should learn to know oneself.’ Self-knowledge will result in a ‘clean, healthy self-love’, a self-love which also implies the recognition of the ‘heaviness of what is one’s own.’ The French lack this ‘healthy self-love’, as well as insight in who they really are. One should not forget that after killing their former king-become-citoyen, the French did not abolish the Guillotine, obviously thinking that, one of these days, their competitor little kings should experience the same fate…

A Nation’s Great Writers

Reading the following, taking into account the difference between prejudiced stereotype and sociological generalisation, one should also acknowledge the wisdom of a nation’s great writers who have tried to give a summa of their own people’s curious characteristics. Reading Molière on the French is an eye opener; the reader should not forget that he already wrote his plays in the 17th century, a century before the French Revolution and before the rancour it produced. That playwright was rubbing it in, highlighting his compatriots’ defects, fileting the general hypocrisy, hypochondria, monetary greed and secretiveness of the French.

When Rousseau, a semi-Frenchman, wrote his notes on the difference between amour propre and amour de soi, he was in fact criticising the French nation – I think – which had not received him well. For argument’s sake, using Karl Marx’s distinction, one might say that self-love as amour de soi is the possession of self, combining the taking care of self and the taking care of others who, being our ‘social context’, are also constituting our own self. By contrast, with the coming of a capitalist-market society, the self became reified and considered as a thing-like entity – a property; a notion which leads to amour propre. Rousseau described amour propre as a constant striving to gauge one’s own ‘comparative worth.’ Likewise, narcissism considers others as things, to be used and abused. Amour propre breeds vanity, mere pride in abstract identities like la gloire Française and ‘being a Frenchman’; this, in contrast with amour de soi, which implies pride in things achieved by oneself.

The French, their State, their Anarchism

The best way to start a description of the peculiarities of French behaviour, is to describe their relationship with socialism. In his La bêtise, André Glucksmann mentions ‘socialism à la Française.’ He claims that it is a pre-Marxian form of socialism, originating in the ideas of Saint Simon with his belief in the beneficent effects of industrialism based on technical progress. However true this may be, Glucksmann seems to miss another important source of the French left, in action often sidestepping its socialism, yet also being an intrinsic: anarcho-syndicalism, which cannot be understood except by reference to the pervasive French ressentiment.

Anarchism is the political creed of revolt; it lacks any capacity to transform from revolt into a revolution, a reason why the so-called French revolutions of the 19th century, and perhaps even The French Revolution, were in fact no revolutions at all. Quoting the American socialist Daniel de Leon on this issue in 1912, a man born in the Dutch colony of Suriname, subsequently emigrated to the USA: ‘Anarchy is the theory of society under which man is a law unto himself. It is a theory of society that finds vastly more affinity with the capitalist class than it does with the Socialist. It is a theory of society that would throw mankind back to the primitive state.’ We might refer in this context to the primitive state which the ancient Greeks called ethnos, the family clan of tribal origin, originating in a purely agricultural/herd-keeping society. At the dawn of classical Greece, ethnos still had primacy over the demos, or the whole of the polis comprising various ethnic entities. Euripides’ tragedy Medea is all about this.

It has become clear from the analysis of the Spanish Civil War, that anarchism is an outgrowth of the farmers’ tendency to revolt – to say no to others, instead of saying yes to themselves. Its support for the democracy, attacked by Franco, was anticapitalistic in a very peculiar way, in that it favoured individual and local freedom over social organisation on the scale of a nation. Even during battle against the army of Franco, anarchists might leave the front to spent a night ‘at home.’ France has fundamentally been, and in a way still is an agrarian nation. By contrast, for example the Republic of the Netherlands was a maritime nation which derived its power from merchants and their shipping business. One might object that by now, a great mass of the French is living in the metropolis; this is true, yet it would not alter my argument. Typically for France is, that even people in larger towns own some property in the country side, a smaller or larger family house in some small village they inherited, something they seriously identify with and to which they will always return when having a holiday of the metropolis. Even in the metropolis the agricultural roots of the French count, including their inherent ‘anarchism.’

Unionism is an important case. At the end of the second half of the 19th century, capitalism in the Netherlands found its ideal-typical form, with a class of capitalists on one side, and nation-wide organised unions of the working class on the other. By contrast, in France unionism has always remained local and dispersed, often leading to strikes in revolt-form, directed against one employer, not evolving into state-threatening general strikes, or becoming a strike against all owners of one type of enterprise. In contrast with England, from the start of French capitalism and its French Revolution, the bourgeoisie has been shut out by the aristocracy, becoming politically closer to the working class than anywhere else, infusing proletarian anarchism with their ‘liberal’ ideas. This combi gave rise to what can be best described as the typical French gilets jaunes type of classless mass revolt; and not to forget, Glucksmann’s ‘socialism à la Française.’

This agricultural base of the French also explains the liaison they have with their state. It is written: God created man in his own image; that may be the case, but in France it was man who created a State of Gods.

.

.

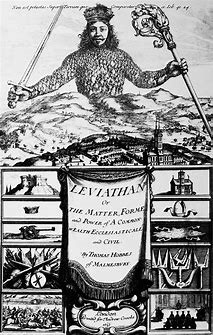

The Brit Hobbes christened the state: Leviathan. Already since the days of Louis XIV did the body of the king coincide with the body of the French State; whoever attacked the State, was attacking Him and vice versa – it was called Lèse-Majesté. The same God ordered Man: ‘Go forth and multiply’; thus, it came to pass. The Body of the French State divided itself in an endless series of State Organs, an immense chain of offices filled with desks, each one of them manned by a mini-God, a functionary who will also be multiplying himself. The Revolution gave all this its extra impetus, the French state bureaucracy had been born. Each of these functionaries of state, each one of these small prothesis-gods, each one of these so-called Civil Servants, is doing what befits a god: in their turn, they create citizens in their image – French citoyens, tamed into subjects, some of them even raised to become their bureaucratic underlings.

In France, whether in each office the computer is working overtime, each god-forsaken resident is permanently bombarded with a never-ending barrage of paper documents which he must fill in and sign with the pen, often in triplo. The French state loves paper. Thus, each citizen becomes a little civil servant himself, risking to commit lèse-majesté by wrongly filling in all the documents, mistakenly or even falsely so – or by simply getting angry at one of the civil servants. Such anger would already be considered as a serious offense against His Majesty, the State. When, after I had bought my ancient house, I had chosen the colour in which my weathered shutters would be painted, petitioned in a 14-page document complete with four photos of the house, the functionary of colours brought out a sample book from the cabinets, which made it clear that my colour was lighter than no. 87, yet darker than no. 88 – it just would not do!

Endlessly making telephone calls to State Organs or helpdesks, plus the filling in of documents have become a Frenchman’s existential obligation, his life’s task. What, in their creative urge, seems to have escaped these little functionary-gods of State, is that their own creatures, the Citizen-Civil-Servants, have yet another task to perform, besides filling in documents and telephoning with State Organs: they must also provide for their livelihood, which for the real civil servants, the lucky ones, coincides with being a civil servant. Here in France, the miserable citizen needs to have a second job. Moonlighting is what the Americans call this; beside the day job of filling in documents, also a night job to make ends meet…

As a result of all this, the French are constantly taking up the hedgehog stance, an antagonistic attitude towards the state, when all prickles are standing out and up: they hate their police force as a real enemy, which indeed treats any citizen in a disdainful way, whatever he does. All functionaries, with the chosen politicians as the most visible amongst them, feel quite aloof from the ones who placed them there, or who voted them in. The French politician will first kiss the arse of the citizen to be elected, to then simply forget about the existence of his constituency and ask them to kiss his arse in turn; once again, amour propre determining their behaviour and attitude. It explains why any Frenchman, once chosen as a politician, changes his behaviour overnight; a real metamorphosis. He starts talking and behaving pompously like de Gaulle did, speaking like an orator in what is supposedly the speech of the gods; he begins with dressing differently, with pomp and circumstance. While they are visibly considering themselves sublime, for an outsider they easily become farcical. Even in the post office, the person ‘helping’ you is acting like a little king/queen, staking out his or her square metre of power, making you unnecessarily wait – rubbing it in that it is a real privilege to be served by them.

French politicians can afford to be aloof, because, as with his vicious objectivity Charles de Gaulle remarked in 1962: ‘The French are each so different, that they are ready to devour one another. It is necessary to find for them a common denominator, which can only be their fatherland.’ But this love of the nation, created by politics, has to be constantly kindled, if not reproduced by that state; it is an artificial love. The same relentless de Gaulle: ‘What has made the free French so exceptional, is the fact that so many of them are property owners. They had to choose between their property – their little house, their little garden, their little shop, their little workshop, their few books or a nice treasure – and France. They always preferred their property. Those who own, are always possessed by what they own.’ Thus, politically and socially, France has been divided into two halves: a vast petty bourgeoisie with, in one way or another, a farmers’ origin, leaning to unpleasant versions of the right; and a working class, also with a farmers’ background, leaning to silly versions of anarchism.

Most Frenchmen, though despising the politicians, would love to be a politician themselves. An example: my neighbour, the great cattle farmer in my hamlet. His father was a famous cyclist, participating in the Olympics, afterwards on the velodrome earning enough on his bike to buy a big farm. He was chosen to be the mayor of our little village. His son, my present neighbour, has always already been talking like de Gaulle, and has had only one purpose in life: to emulate his dad (which he couldn’t) and also to become mayor. The people despised him so much, that they asked the last mayor to come up in one more election; the neighbour was clobbered. Now he despises all others, as well as himself.

The French and their Curious Conviviality

As the same General and President de Gaulle once phrased it cynically: the French are ready ‘to devour another.’ When they gather in protest, they most often form a disorganised crowd of individuals, a mob as was to be seen when the gilets jaunes took the streets; a gathering of people who deem some sort of protest or revolt necessary. The only way in which the French may be subdued into a well-directed, organised multitude, is when the state has taken over the management of their behaviour, transforming would-be anarchists into docile citoyens, as for instance in the army. Paradoxically, the fixing and following of rules in some way linked to the state, is the anarchist-citizen’s heartfelt duty and pleasure; until, of course, his anarchist urge takes over. French behaviour tends to be always propre, docile, clean and befitting, even in the waiting rooms of doctors. Where in any other country of the world, people facing death have lively conversations, the French sit there like wooden ducks to be shot by the ‘man in white.’ Only when people really ‘drop out’, thoroughly bum-like appearance and behaviour take over – decorum ends suddenly and completely.

Non-state social rules show the same paradoxical combi of being strict, as well as manipulable. The typically ‘southern’ notion of clientelism has taken solidly hold of the French soul. The more fixed and inflexible the rules, the more easily they are corrupted by people, happy to oblige friends and family. An exemplary case, archetypal because ‘foreigners’ were involved, and for the French foreigners as such can never be part of the ‘in-crowd’ of relevant others. A Dutch couple had just bought their French summer house. They invited a mason for coffee, when it was agreed that in April special tiles from the Mosa factory in Maastricht would be shipped to their little hamlet, stored inside the house on the main floor, which was then to be tiled by the mason in May. With great expectations, the couple arrived in July and found their house a mess, the ground floor occupied by endless stacks of the special tiles, not one of them placed… A phone call ‘cleared up’ matters; the floor of the brother-in-law of the mason ‘suddenly’ had to be done first – ‘You’ll understand.’

Fundamentally, the French have been postmodern before postmodernity even arrived; rules are there for ‘the others’, not for ‘me’; when under inspection, they follow them, which in an étatist nation like France sometimes means intensely so; or they do not follow them at all. As there is a shortage of police personnel in many of the smaller towns in la France Profonde, having escaped the surveillance of their parents, the younger generation does what it likes to do, which is being a nuisance. Parking behaviour is another case in point. If it is safer for your car not to park on the road, just park it on the pavement, so pedestrians are less safe…

.

.

The contradictory anarchism of the French will tell them, that if one of them goes against the rules, all others should be deviant in the very same manner. Of course, on market days, when some policemen are around (if only to show that they really exist), everybody is rule-precise, drivers not in the least holding back to tell other drivers that they do not follow the rules properly.

On the highway, the French behave accordingly. They drive you off that road, almost moving their car into the boot of yours, whatever the speed permitted (no one, so it seems, keeping to that speed); then to pass your car, to immediately slow down again, so that now you have to slow down in turn – at their pleasure. After all, who the hell do you think you are, driving in pole position! Precisely the same behaviour is found in any French situation which involves queuing of one kind or another; waiting in line for the cashier in the supermarket, one is sure to feel the cart of the person behind you bang into your heels. You should not have been there in the first place, as any Frenchman would-be king/queen would have liked to be in front of you, considering this his/her rightful position.

On the scale of French values, conviviality is ranked high; even after reading Nietzsche, no French superman would ever re-valuate that principle. Yet, no jealous grievance-monger of a Frenchman can stop to be unsatisfied, even complaining at social gatherings, never really full of joy in their conviviality. A rather large pastice fuels his burning desire to feel dissatisfied and to make clear that this is not a good world; not his salary, nor his future pension; not the policies of the state; not the behaviour of others (from which, just for the time being of this little convivial gathering, he will except present company) – et cetera. A Frenchman always seems to be a little bit angry, a little bit excited; the language has suffered the consequences and has been malformed, become sharpish, cut-short, high-pitched and always a bit indignant. A Frenchman is overly curious as to his neighbour’s money, habits and mishaps, while he is very much caché as to his own things, as well as his own self, hiding them away, not telling the other a thing; the risk that one little king turns out to be a lesser little king than his neighbour-king is too great. Whereas in the Netherlands, behind large windows curtains are left open, in France shutters over small windows close off the individual’s world. Even in newer buildings, windows are incredibly small; Le Corbusier may be a French hero; his architecture with the large glass windows is not practiced at all.

Dogs, Weeds and Puritanism

The French are hypochondriacs, talking about their afflictions as if they should not have had them, or on the contrary, that about their very special afflictions which make them deserving of your extra attention. Life seems never to be what all of them suppose it to be as an of course: healthy and clean. The French feel their illnesses as an affront, just as the notion of a French nation implies the existence of a pure Frenchness; racism and xenophobia are everyday phenomena. Not, that they are not aware of the stains; on the contrary. However, the bottom line is that foreignness is staining what is, and what will always remain an essentially pure ‘Frenchness’, foreign influences being experienced as the cause of all evil. French puritanism does not seem to be sexual; it is ethnic and racial.

More generally, the French want everything to be propre and neat; observe their clipped topiary, their spotless lawns and idem borders, their finicky manner of dressing by both males and females (even to be casual, one should yet be… propre). Any Frenchman will point out to any foreigner that, what for this foreigner seem to be lovely little flowers or cute little green leaves in his garden, are mauvaises herbes – weeds to be immediately cleared out!

Finally, the clinch: French dogs. Whereas in The Netherlands and in England a dog is first of all a companion, a four-legged friend, in France its function of a chien méchant dominates such friendship. The French dog is a watchdog, an animal which must keep out what is alien as such, that is: other Frenchmen and foreigners more generally. When a Frenchman meets another Frenchman ‘walking his dog’, he expects his and the other man’s dog to immediately start barking in a vicious way; the town is continually sounding like an asylum for mad dogs fighting one another. Walking in the countryside, which few Frenchmen do themselves, but also walking past large gates and hedges guarding the town houses: beware! From unexpected corners of farms, or from behind hedges, wild and vicious animals may jump at you, screaming.

.

.

The French, whether in the countryside or in town, are always defending themselves against other Frenchmen – the real aliens.

And last but not least: the Fifi-dog, which is a wholly and unholy affair of French women; those insect-dogs, which they cuddle and talk to as if it were their lovers. They too are continuously yelping at strangers; barking is not the right word.

.

.

With their insect-dogs these women, perhaps sexually dissatisfied and never ready to tell a thing about themselves, do so in a round-about way. One always suspects these ghastly little animals to be cunt-lickers, as the French painter Boucher already painted them so well in the 18th century.

.

.

What is more, if they do not want to show off these dogs themselves, most of the women abuse their husbands to actually ‘walk’ the little beasts, perhaps too exhausted as they are from having abused the animal in the Boucher way.

Mimicry

By now, my reader will have guessed the plot of this essay: your writer has become so assimilated in his surrounding French world, that mimicry has become his fate. Like the French, he has become a grievance-monger, spitting anger at the Frenchmen around him, even writing a longish essay on The French, in a Friesian’s Perspective… Then again, it is only a case of partial mimicry: I have not become jealous of my French compatriots; they have nothing I would like to have, or that I would like to be.

.

Sierksma, Montmorillon, 1.5/2024